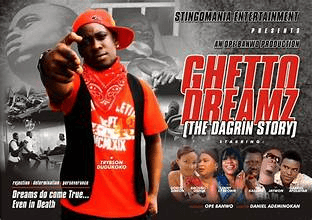

Stingomania Entertainment presents Trybson Dudukoko (Dagrin), Kayode Odumosu (Dagrin’s Father), Rachel Oniga (Dagrin’s Mother), Doris Simeon Ademinokan Chichi), and Gabriel Afolayan (Onome). Director of Photography, Yemi Awoponle; Producer, Ope Banwo; Executive Producers, Ope Banwo, Bashiru Adeboyejo, Lateef Orisumbare; Director, Daniel Ademinokan; Producer/Screenplay by Ope Banwo. © 2011.

This is the story of a young Yoruba rap singer whose blooming musical career was wilted by nature before reaching maturity. Compared to our American artists, Olaitan Oladapo Olaonipekun (Dagrin) is in line with Tupac Shakur: both lived wanton, unregulated, and careless gangster lives. They both had the same dream for music and served that purpose, but both lives were cut short by accident. Indeed, Dagrin’s ruggedness is almost like the life Tupac led. Here is Dagrin, whose female teacher could bring him to the headmaster’s office to be scolded. “Sir, I’ve exhausted all the tricks I know in the book to train a dull student….” “His case is pathetic.” Concludes the headmaster. You can’t change anything about a boy in class, fantasizing about a nightclub or bar crowd, and hawkers on the street singing and dancing to his song, while the teacher tries to drill into his distracted mind what an equation in algebra is.

Ever since his father dismissed him as a no-good child who could fail all subjects except Yoruba, Ola never cared. Dagrin’s Mother (Rachel Oniga RIP) negotiates and handles the fragile relationship between Ola and Dagrin’s Father (Kayode Odumosu) because of Ola’s neglect of schooling. When Ola had failed in all his classes except Yoruba, the father yelled at him:

“Get out of my sight before I break your head. Empty Skull!”

Dagrin’s Mother, “As a parent, you can’t disown a child because he is stubborn. It is true he is hard-headed. But if you look at it, the words you said to him were heavy and troubling.”

“You know that I don’t agree with his dirty habits.”

Mothers are advocating for the protection of their children.

“I’m not saying you should not scold him…when you use one hand to scold him, use the other hand to pull him closer. Let’s not be so hard on him that he will leave…I beg you (Kneeling).”

After arguing with his father, Ola leaves home and joins Onome (Gabriel Afolayan), a ghetto leader who introduces him to the gang. The gang had greater faith in Ola’s talent. One gang member could comment: “The voice of man (Ola) is the voice of God. This boy is going to blow.” Another comments, “You’re on track like a big boy…when chin-chin go drop the money, you become the bling-bling.” The gang trusted Ola. With his departure from home, he now has ample time to record in studios. Soon, Ola could cut a single with the help of his girl Chichi (Doris Simeon Ademinokan), a twenty-five-year-old flame, older, who financed the production. There is, however, one problem with Ola’s output.

Production houses are not responsive to Ola’s Yoruba ethnic recording, and they run him off their premises everywhere he goes and dismiss his song as non-saleable or with no audience. The studios could not accept his kind of Yoruba rap music. Remember, the only passing grade, and, as a matter of fact, the last, he had in school was in Yoruba. The collective discordant noise of the gainsayers couldn’t dent the fire he had to make himself a success, even as he could do so posthumously. One couldn’t understand, but this young Yoruba prophet in the realm of Kuti had a message to deliver, maybe not quite timely or appropriate for the present generation, he vividly expresses himself in his mother tongue.

Ola and his godbrother, Otome, trucked from studio to studio without luck. As genius could strike in that big head of Ola, he comes up with the idea of a ground-level promotion: go to the market, sell your stuff to the market women, sell your music to the stalls, to the Danfo buses. These are ordinary people. They’ll understand you better and even faster. That’s what he did. Soon, his music was on the lips of everyone, including hawkers, market women, passenger buses, and, I mean, everywhere. Overnight, Ola becomes a success. There are scenes in Ghetto Dreamz that I take away: The scene when, for the first time in his life, Ola brings home to his mother the reward he got from the outer world.

Ola’s Mother, “Oladipo, where did you get the money to buy all these things?”

Dagrin, “Through your prayers, I’ve secured some shows. The small amount of cash I received is…”

“Thank you, I’m grateful. (sets gifts on the seat) Oladapo, thank you; your children will not abandon you. (Beat). What about your education? Do you attend church services? … I want you to get closer to God, because whoever does this could not be put to shame. Everything you do will be successful…because (pointing to the sky), God is the Alpha and the Omega.”

I admire the way the producers and cinematographers presented Ghetto Dreamz. They wanted Dagrin’s death to extend its gloomy pall over all us; to strike us, to smoother us, so they telegraphed it in a Cinemascope, Panavision, Vistavision, and all its scopes and visions, and Letterbox design. But before I get you confused, let’s call it, plain and simple, Widescreen. See the screen’s width, which has hardly ever been seen in other recent Nollywood productions. Using this type of screen immerses viewers into the action. I feel part and parcel of the mourners lined up at the thoroughfare to pay their last respect to Dagrin. Their tears and mournful faces, and wailings got me to shed a tear or two when the coffin of Dagrin came close to my face. The shots cover the length, breadth, and width of the funeral processions, well-wishers, and their teary, mournful faces. That is the magic of the panoramic shots of widescreen.

The other scene is when Chichi and Ola (Dagrin) are left in the room. Despite her persistence, they did reality checks: Ola refused to meet her parents regarding their present relationship. Ola, too, couldn’t trade his dream for anything, lest he marry or trade anything for a penny. That’s the last time Chichi could get together with Ola, besides running into each other at the hotel entrance one day. She had gone on to date a rich guy, and Ola had become a successful artist. The duration of Dagrin’s life was brief when it was (no metaphor intended), taken at midfield.

Reckon the landscape shots of the movie? A magnificent design! The shot of Omone (Gabriel Afolayan) walking a long distance from his side to the opposite side of the street. That could only be possible in a widescreen, landscape design shot. It doesn’t have to be cut. This one straight shot covers such a distance and all its surroundings. Matter of fact, that walk is emblematic of the Nollywood Walk of Fame. Observe Omone’s hustler kind of walk, by every measure, his strides, and Mojo walking, with the camera remaining stationary but tracking him from behind as he crosses to the opposite side of the street. As little as this scene could be, in the grand scheme of Ghetto Dreamz itself, that’s a Master Shot!

In every society and each generation, there is always a social incident that catapults the succeeding generation into making up for what the preceding generation left behind. That could be a song, slang, and dress code. I never wore a jacket, we called, ‘sand-sand boy.’ (It was a code that identified native diamond miners in the Eastern province of Sierra Leone. My generation scorned them. You guess. I swore I never wore one). Fela Anikulapo Kuti introduced Afrobeat and overcame many challenges to bring his music to Nigeria and the world, paving the way for artists like Olaitan (Dagrin). At first, society couldn’t accept Kuti’s introduction of Afrobeat. The genre combines West African music with American funk and jazz, into mainstream Nigerian music and the world. Most Nigerian producers expected Dagrin to speak in the universal (English) language, but he raps in Yoruba, plain, raw, unvarnished, and straightforward. Today, everybody celebrates Kuti in Europe, America, and the world. Nigeria celebrates Olaitan (Dagrin) as the kid who, despite the collective discord and all impediments, brought the Yoruba rap to mainstream Nigeria, posthumously, though, in the vein of Tupac and Biggie. The musings in his music and song waft an everlasting fragrance on the Nigerian youths to this day.