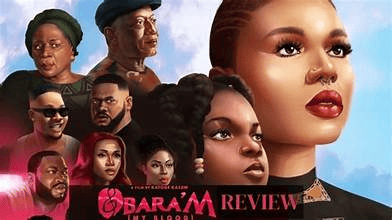

Film Trybe, Nancy Isime (Oluchi), Nkem Owoh (Humphery), Deyemi Okanlawo (Fedelis), Darasimi Nadi (Iheunaya), William Benson (Bishop). Director, Kayode Kasum; Executive Producers, Kayode Kasum, Kene Okwuosa, Dare Olaitan, Moses Babatope, Odunago Ewaniyi, Craig Shurn; Co-Executive Producers, Mimi Bartels, Adora Nwodo; Director of Photography, C.S. Ifeme; Screenplay, Stephen Okonkwo. © 2022.

With all its dramatic twists, turns, and bumps, leaving behind a long trail of tears, Obara’M happily ends with a resolution not found in most productions. It ends excellently, with all plots concentrated into a solvable conclusion and, most importantly, an upbeat ending that leaves the audience with uplifting music and song. I had just reviewed One Bad Turn (2022), which left me with a depressed feeling and a damp soul. I needed some uplifting story, something warm I could cozy up to. Imagine I danced to the song at the end of Obara’M, film. I would have preferred the end music of Wedding Party Reloaded (2017), page 81, Nollywood Movie Reviews Vol 1, to give us such a lively tune at rolling the end credits, one I can sing in the rain. The underlying power of Obara’M is music and song, and it ends rightly so. Beautiful composition.

I will wipe my tears and wallow in this narrative with you; you only must strap in because the road will be bumpy. Hold on to your tears, you lovable viewers. It is heart-wrenching in most places, but it is only a movie. Oluchi (Nancy Isime) is Humphery’s (Nkem Owoh) wayward daughter living on the streets. She is a wannabe singer. Oh, she sings, no kidding. But she flirts with drugs and drug dealers, hangs out with Fidelis (Deyemi Okanlawon), a student, and abandons him for being poor, even as she carries his seed in her womb, for another man, who claims to have all her answers: a tile laden mansion, door key and lots of drug money. This new guy is a big-time drug dealer. Not long after, he is taken to prison. Oluchi is left with pregnancy and on the street. She goes back home to her father, Humphrey, where she has a baby girl, and her father names her Ihunaya.

Because of Oluchi’s wayward behavior, the grandfather, Humphrey, takes the little girl as his own until the older man passes due to high blood pressure. Yet before his passing, he had spent his prescription money, immeasurable love, and care to pay for Ihunaya’s (Darasimi Nadi) schooling. It pays off well. The little girl proves smart and wins a 250,000-naira scholarship to secondary school—money well spent.

Meanwhile, Oluchi joined a band with Ihunaya, towing behind and singing with her on stage. The new glory or sensation doesn’t last when the drug-runner boyfriend from jail interrupts it, blowing Oluchi’s cover, as prostitute, and hence, she runs from there in shame.

The award Obara’M received at the 2023 African Movie Academy Awards for Young Promising Actor for nominating Darasimi Nadi was quite in place. In passing, I will withdraw my once-false accusation that Nollywood doesn’t use kids in movies. Destiny Etiko and William Uchemba, now grown and doing adult things, came through the Nollywood pipe. I beg. With Nadi, Nollywood does well to have hired her service. Her acting is excellent and promising. Imagine her exchange with her father and parallel it with Amy, (Hanna Wanjiku), that South African child actress, in An Instant Dad (2023) when her father isn’t ready to accept her: “I’m your daughter…. Then there’s something wrong with me. Why, then, don’t you love me?”

In Obara’M, Fidelis presents the DNA result to Ihunaya:

“what is this?” She asks.

“It means Ihunaya; I am your biological father.”

Ihunaya moves to hug him, and she is rebuffed.

“but I cannot accept you as my child just yet.”

“Am I your child or not?”

“The paternity test says so, and you are. But I have a family of my own.”

“Are you rejecting me?”

Fidelis tells Ihunaya he will sponsor all her schooling and care. And this is what Ihunaya says:

“I don’t need a sponsor. I want a father.”

The cinematic scene between Oluchi and her dead portrait talking to her is memorable and becomes the turning point in the story. Humphrey has always tried to show love to his daughter, though reluctantly, like most African fathers do, holding their fatherly ground. In that scene, with low lighting, his spirit, like when he was alive, talks and warns his loving daughter: “God walks in mysterious ways. God communicates with people in different ways. He even sends messages in different ways, through visions, dreams, interaction with people, relations and friends, and even foes. You must identify your message, decode it, and move on for those of you who mistake it. You’ll waste your time, and it will be dark. The world does not wait for no man or any woman. Make haste.” Humphrey must be speaking to you. No, me.

After this scene, Oluchi comes out singing a song of deliverance. She goes about making amends. First, she goes to Fidelis’s family home and confronts Fidelis about his daughter. The cinematic moment in the scene is when Fidelis, from his upstairs balcony, locks eye-to-eye down at Oluchi in the middle of his downstairs living room for the first time since after ten years he almost got run over by her boyfriend, who takes her away from him. Those short seconds of a look say so much that a scribe could create an entire scene from it.

He is not readily acceptable and must undergo DNA testing to be sure Ihunaya is his blood. He is the girl’s father, but Oluchi could not accept the check he gave her. He was still hurt when Oluchi abandoned him for a drug dealer. “Oluchi, I cannot accept Ihunaya; I am happily married with two kids. I cannot accept Ihunaya without affecting my marriage.”

“But she’s your child.”

Fidelis, almost crying, says, “I didn’t raise her. You stole her from me. You stole me from her, and because of your decisions, I’m forced to make the most painful decisions of my life.”

“You are making a mistake.”

“I know. And I have no intention of destroying my marriage.”

Oluchi tears the check Fidelis gives her to raise his kid to shreds and spits on it.

She goes on to amend with her band. She had been thrown out for stealing from them. Now, it’s back to seeking forgiveness from the group. In this scene, Oluchi comes face to face with her past as she addresses the band, where she has lost their trust. “I feared failing; of being poor. I abandoned my papa. I abandoned my child because of this money…and the small family I had in Lagos; I still abandoned you guys. I cheated on you. That’s why I’m here today to apologize. I am sorry. Please forgive me.” She drops 800,000 nairas, checks on them, and leaves. She later visits her father’s grave, and reunites with her aunt and daughter, Ihunaya.

Oluchi must have tired of running like we all did when we strayed so far from the clutches of things that bind us to our heritage and dear friends; I could be one. That makes Obara’M human story. Guess why I say so. Oluchi has been running all along from the poverty she inherited from her father–like some of us have shamelessly done at one time or another––-denied her belly-born daughter and impersonated her for a younger sister––Yvonne Okoro in Single At 40 (2023) denies her daughter. She cheated the only friends and group she had come to call home in Lagos.

Can’t you see the humanness in her? Oluchi fell off the train of life into the gallows of sin, but she repents. She was born with these gargantuan ambitions but sees what life throws in her path: a poor father and a daughter when she had barely turned eighteen, and a dream career to be a singer, not going anywhere; all the ugly strappings that would make one look back at their life, and sees reasons why someone would noose their necks in a backyard alley and not mind what the world would say about them. Maybe I am rubbing it in too hard for Oluchi, which, besides her excellent acting, which I had no qualms with, matter-of-fact marveled, really pressed my emotional buttons.

As the title in the Igbo language signifies, a stream of blood runs through this movie. As nature could have it, all the gods came to Oluchi’s side. She goes about visiting her father’s grave (blood), uniting with her daughter (blood), and getting Fidelis (blood) to go into her daughter’s life. As she completed this rite, her life had meaning. A long-time recording of Oluchi’s song was accepted and played everywhere on the radio waves. She became successful in her singing career. Maybe I can do the same. As a creative loafer, I hope to go on, pour libation on my mother and father’s graves and turn round, raise my hand to the sky, and ask for their forgiveness. Maybe, just maybe, the God of heaven will grant my prayers and get me out of this creative darkness.