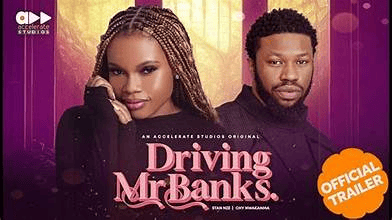

Accelerate Studios present Chy Nwakanma (Hauwa), Omeche Oko (Jessica), Stan Nnze (Yormi), Harriet Akinola (Rachel), Somto Eze (Collins), Joseph Ossiegu (Ken). (Director of Photography, Oluwamayowa Lawrence; Screenplay, Eyo Emmanuel; Producer, Blessing Obasi Nze; Director, Harry Dorgu; Co-Producer, Vincent Nwachukwu. ©2024

Driving Mr. Banks is a title that got me looking forward to watching Saving Mr. Banks––yet to come out. Tom Hanks’s production is more reminiscent of the American establishment’s glory days by the turn of the Century. We can leave Saving Mr. Banks and engage ourselves with today’s issues––Driving Mr. Banks. Or better yet, we may think of Driving Miss Daisy (1989), when Hoke Colburn (Morgan Freeman), a negro is hired by a Jewish elderly widow, Miss Daisy (Emma Thompson), as a chauffeur to drive her around. Check out the quirks, cultural differences, and nuances that creep out of Black and White on a several-hour road trip. Yet, eventually, they both realize they have more in common than what separates them.

The differences between Mr. Yormi Banks (Stan Nnze) and his driver, Hauwa (Chy Nwakanma), aren’t based on race, skin color, or upbringing. Mr. Banks is the CEO of a company (not made explicit in the movie) that has a debilitating health condition––Parkinson’s disease. He comes downstairs from his office to the lobby and enquires about his taxi driver from the receptionist. An Uber Eats deliverer is present and serves as Mr. Banks’s driver. Her acceptance to drive for Mr. Banks is the expository scene of the entire story––the Alpha and Omega.

As a CEO, Mr. Banks couldn’t drive himself to work and relied on ever-disappointing taxi drivers. Then, he walks in on Hauwa, the Uber Eat delivery driver who happens to volunteer to drive this stranded CEO to work daily. The CEO is stranded for a reliable driver.

Driving Mr. Banks isn’t as easy as it seems. He has Parkinson’s disease and doesn’t want, not his company, his friends, or anyone to know, and Mr. Banks suspects Hauwa knows about his illness, so he fires her.

I don’t quite buy into Mr. Banks’s literal, structural mechanics. This could be a formula movie. One of those when two high school kids, on their first day, butt heads in the hallway as the boy helps a girl pick her books off the floor; twenty-five years later, both visited the school’s homecoming as Mom and Dad. It seemed coy when an Uber Eats deliverer walked into an office and left as a driver for a company’s CEO. To film buffs, you can grab the film from there onwards, and in most cases, some viewers would take leave. I am not saying there are no natural occurrences of meeting and crossing paths with strangers and forging relationships in real life. But in Driving Mr. Banks, this kind of meeting between Hauwa and Mr. Banks is obvious, and the film is reminiscing about the daily diet of third-grade films Nollywood dishes out to the viewing audience.

Stories of acclimations won’t have to be noticeable and assume their summation all in a single shot, as in the lobby scene where Mr. Banks first meets Hauwa. Hit me on the side of my head with a baseball bat. Yes, you. I do. But it is too apparent, with a disjointed nerve ending besides the scanty meat on the bones; for instance, the film starts with a character afflicted with a disease that no medical field in the country has gotten hold of. The movie would have overplayed its hands on that. It should blow it up to take a life of its own. However, when the film brings in misdiagnoses of his affliction, we are happy for Mr. Banks, but I would have loved him to battle with the disease a little longer.

With no comparison in mind between Driving Mr. Banks and Miss Daisy, the latter never hastily runs through telling its story. It took years, approximately twenty-five. Mr. Banks’s relationship with Hauwa, from the time they met in the lobby to the consummation period, did not gather much backstory that would have added meat to the bone. Granted, Hauwa discovered Banks’s affliction with Parkinson’s, and he wants to keep it away from the world:

Hauwa, “Whatever I did, I am so sorry, Sir. But I need this job…about Parkinson’s; I won’t tell anyone about it, I promise.”

Banks, “Excuse me?”

Hauwa (demurely), “My mother used to work as a caretaker in a nursing home, so I’ve seen few people with the same disease. And from your symptoms, you are in the early stage.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Mr. Banks starts to close his door in her face, but she manages, with her head in the frame, to say:

“Sir, the accident. It wasn’t because you didn’t have your glasses, wasn’t it?”

(A beat, demurely), “No. I had a tremor, and I lost control. What do you intend to get out of this? Money?”

“No, Sir, I wasn’t raised like that. But I need this job, and you need someone you can trust.”

(Thoughtful), “No one can know about this.”

“No one, Sir.”

In Driving Miss Daisy, the son is forced to hire a driver, Hoke Colburn (Morgan Freeman), for his mother, Daisy Werthan (Jessica Tandy), after crashing her car. For Miss Daisy and Hoke, teaming up as hired drivers and Mistress Daisy, it takes almost years before they finally come to terms with each other, even to the point of romance. Hauwa and Mr. Banks’s relationship didn’t take long before they became friends and finally soaked pillows with tears for each other.

Banks and Hauwa had something in common–the need for outside help in each other’s personal lives. Hauwa is from a broken home, and she and her mother barely make it. She wants help with the bills and is seemingly the breadwinner for her and her mother. She throws herself on Mr. Banks to be his driver, which by cunny, she gets. Besides Mr. Banks, no one of his family members is present except in the flashback. He needs a character next to him, and through his relationship with Hauwa, his character is suitably dramatically beefed out.

I am not in the business of hawking films or appending stars to pictures. I am not an all-knowing and all-seeing. I’m human and therefore subject to overlooks, mistakes, and miscalculations, but Driving Mr. Banks is a regular movie with no juice besides. I review, analyze, and criticize as honestly as possible and find nothing exceptional about the picture. I have seen the lead player Stan Nze in Afemefuna: An Nwa Boi (2023) and admire his performance, but here, no. I won’t blame him for what he is here in Driving Mr. Banks; screenplays usually tie characters to a standard, which is what they play. Mr. Banks has Parkinson’s, but the affliction didn’t last, and therefore, the sympathy we had for him in the beginning wears away by the film’s end. Indeed, the writer toys with our emotions. What if he had thrown a glowing light on Parkinson’s and its devastation, as did Diamond in The Sky (2018)?